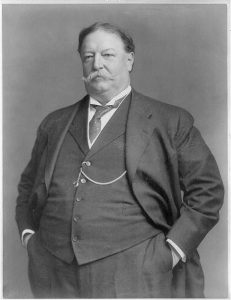

After my last blog on obesity and the ADA* Robert Taft, a subscriber who as far as I know is not related to the fattest U.S. President, William Howard Taft, was kind enough to point out several pending decisions that are likely to affect, if not clarify, the problems related to obesity as a disability. Today we’ll take a look at those cases and the influence they might have.

After my last blog on obesity and the ADA* Robert Taft, a subscriber who as far as I know is not related to the fattest U.S. President, William Howard Taft, was kind enough to point out several pending decisions that are likely to affect, if not clarify, the problems related to obesity as a disability. Today we’ll take a look at those cases and the influence they might have.

In Richardson v. Chicago Transit Authority, 17-3058 and 18-2199 (7th Circuit) the Seventh Circuit will answer, for cases in the Seventh Circuit, the question addressed by the Velez case discussed in my last blog on this subject. Velez identified two possible standards for determining whether obesity is a disability. The stricter standard was adopted by the 8th Circuit in Morriss v. BNSF Ry. Co., 817 F.3d 1104, 1108 (8th Cir. 2016). That case holds that obesity is not a disability unless the plaintiff’s weight is both far outside the normal range and caused by some other underlying physiological disorder or condition. It rejected the idea that the 2008 amendments to the ADA expanded the definition of “physical impairment” and therefore relied on earlier cases from the Sixth Circuit [EEOC v. Watkins Motor Lines, Inc.,463 F.3d 436, 442–43 (6th Cir.2006)] and Second Circuit [Francis v. City of Meriden, 129 F.3d 281, 286 (2d Cir.1997)]. Velez itself adopted a more liberal standard is found in the most current EEOC documents, which provide that obesity can be a disability if it is sufficiently outside the normal range regardless of cause. In support of this approach it cited a number of district court decisions from other Circuits. Of course these lower court decisions do not bind any other court; even other district courts:

“A decision of a federal district court judge is not binding precedent in either a different judicial district, the same judicial district, or even upon the same judge in a different case.”

Camreta v. Greene, 563 U.S. 692, 709 n.7, 131 S.Ct. 2020, 179 L.Ed.2d 1118 (2011).**

It does not appear that any Circuit Court has adopted the more liberal standard, so a decision for the plaintiff in Richardson will create a clear split in the circuits and provide important ammunition for obese plaintiffs in all but the Second, Sixth and Eight Circuits. Right now a decision is not imminent, for on January 10 Richardson asked for an extension of time to file his reply brief and the week before the court permitted the filing of a number of amicus briefs. It seems unlikely the Court will digest that much material and set the case for oral argument any time soon.

Shell v. Burlington Northern Santa Fe Railway, 18-8027 (7th Cir.) presents essentially the same question as Richardson but is an appeal from a decision in favor of the plaintiff instead of against him. The case is in its earliest stages and so it is likely Richardson will be decided first.

Finally, Taylor v. Burlington Northern R.R. Holdings, 16-35205 (9th Cir.) presents the possibility of a two for one result. The plaintiff claimed discrimination under both federal and state law. The case has been certified to the Washington State Supreme Court so the federal court will know what the state law is before proceeding to a decision on federal law. The Washington Supreme Court will hear oral argument on February 28, and the Ninth Circuit won’t act until it hears what the Washington Supreme Court has to say, so any decision is likely to be months away. It is possible that if the Washington Supreme Court finds that under state law the plaintiff is obese the Ninth Circuit will decline to make any decision about federal law because the plaintiff already has a state court remedy.

Where would President Taft fit in this debate? With a Body Mass Index of 42.3 Taft would be considered morbidly obese today.‡ I couldn’t find any indication of a physiological cause for his weight, so in the 2nd, 6th and 8th Circuits he would not be considered disabled for ADA purposes. A number of district courts would find his weight alone qualified him as disabled, but no Circuit court has adopted the more liberal interpretation of the ADA. Later this year we will probably find out what the Seventh and Ninth Circuits think about the issue, but unless and until the United States Supreme Court rules on the matter it will remain the subject of argument and disagreement, something that provides both benefits and risks for businesses sued under the ADA.†

* Obesity and the ADA: Who is disabled and when does it matter

** My blog and others spend a lot of time on district court level decisions because that is where the action is for ADA and FHA disability rights claims. It is worth remembering, however, that any federal district court judge can go his or her own way unless the Supreme Court or his or her own Circuit Court has ruled on the issue.

† As a final caveat, it must be noted that these are all employment cases brought under Title I of the ADA. For cases brought under Title III it may be hard for an obese plaintiff, even if found to be disabled, to prove a violation of the law because the ADA architectural standards simply don’t address the needs of the obese except indirectly when their obesity confines them to a wheelchair.

‡ For the sake of comparison, our current president, with a BMI of 30, is merely obese. James Madison, the lightest president, was underweight at 122 pounds and a BMI of 17. All statistics are from presidenstory.com