In the last two years the federal courts have had a number of opportunities to find that Title III claims under the ADA are not arbitrable and have declined the invitation. That doesn’t mean these cases are in fact going to arbitration. In every case I found the arbitration agreement was found to be unenforceable on state law grounds, leaving open the possibility of a public policy argument. Nonetheless, I think that a properly written and implemented arbitration clause can force a Title III case into arbitration and give defendants a chance to avoid much of the unnecessary cost of litigation. Here’s why.

In the last two years the federal courts have had a number of opportunities to find that Title III claims under the ADA are not arbitrable and have declined the invitation. That doesn’t mean these cases are in fact going to arbitration. In every case I found the arbitration agreement was found to be unenforceable on state law grounds, leaving open the possibility of a public policy argument. Nonetheless, I think that a properly written and implemented arbitration clause can force a Title III case into arbitration and give defendants a chance to avoid much of the unnecessary cost of litigation. Here’s why.

The starting point in a discussion of arbitration for civil rights statutes has to be Gilmer v. Interstate/Johnson Lane Corp., 500 U.S. 20, 111 S.Ct. 1647 (1991). In Gilmer the Supreme Court found that claims under the Age Discrimination in Employment Act could be made subject to a valid arbitration agreement, rejecting claims that it was somehow inconsistent with public policy. A few months later Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1991, in which, among other things, it affirmed that

Section 118, as quoted in Lambert v. Tesla, Inc., 923 F.3d 1246, 1249 (9th Cir. 2019). In Lambert the Ninth Circuit concluded that the 1991 Act could only be read to support the arbitrability of civil rights claims. Equally important, the few decisions considering the arbitrability of ADA claims outside the employment context agree that they are subject to arbitration. See, Bercovitch v. Baldwin Sch., Inc., 133 F.3d 141 (1st Cir. 1998) and Cheshire v. Fitness & Sports Clubs, LLC, 382 F. Supp. 3d 1329, 1334 (S.D. Fla. 2019). There is clearly no public policy or similar reason why website accessibility cases should not be subject to arbitration.

Of course, before a defendant can compel arbitration of a claim it must prove that it has an enforceable arbitration agreement. The difficulties of making such an agreement were explained in Natl. Fedn. of the Blind v. The Container Store, Inc., 904 F.3d 70 (1st Cir. 2018), a case that nonetheless supports the view that website accessibility claims can be subject to arbitration. In Container Store the arbitration clause was contained in the terms and conditions for The Container Store’s customer loyalty program. When blind customers sued claiming that touch screen point of sale devices violated Title III of the ADA the Container Store tried to push the claims into arbitration.* The plaintiffs fell into two categories. One group had signed up for the loyalty program at a touchscreen POS device in the store. These customers could not have read the terms and conditions, being blind, and denied that the terms and conditions had been read to them. The Court had no trouble finding there was no assent to a contract whose terms they did not know, but left open the possibility that a summary of terms might have sufficed if actually read to the customer. A last plaintiff had signed up on line, where the terms and conditions appeared in full and were accessible to the plaintiff’s screen reader. This plaintiff could not claim there was no assent to the contract; instead the Court found the agreement was illusory because The Container Store reserved the right to change any of the terms and conditions at any time. Such provisions are not uncommon in on-line agreements, for businesses want the flexibility to revise their marketing programs as they need to. The defendant lost in Container Store, but the opinions of both the District Court and Court of Appeals make it clear that if you do it right it is possible to compel arbitration of Title III claims.

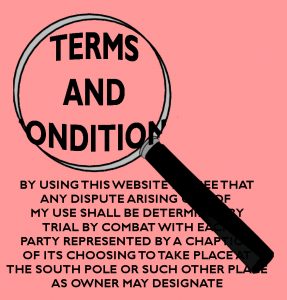

How do you do it right? The first step is to avoid the argument that the arbitration agreement was not accessible. No matter what other accessibility problems a website may have it should make access to the terms and conditions of use easy for every disabled person. Next, of course, the arbitration agreement has to be part of an enforceable contract. The safest way is certainly to require a click; that is, a positive act showing assent to the arbitration agreement. The District Court in Container Store wrote:

Natl. Fedn. of the Blind v. Container Store, Inc., 2016 WL 4027711 (D. Mass. July 27, 2016). This would be simple enough except for one thing. In Container Store the plaintiff was not merely using the website; she was signing up for a program that promised something in return for enrollment.**