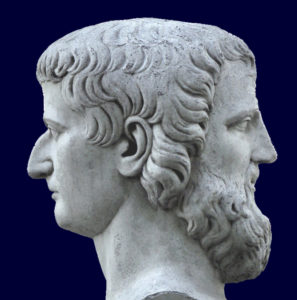

Janus, the two headed god that looked to the future and past and gave us the name for January, wouldn’t find much new in the world of disability law if he were contemplating 2023. Cases from the last few weeks look pretty much like cases from the end of 2021 and the end of 2020. Serial ADA litigation is going strong because outcomes depend on the judge assigned rather than the law or the facts. Sober living homes continue to create hostility and litigation as politicians try to balance doing the right thing against the demand of their constituents that they do the wrong thing. And, of course, the cost of victory is often much higher than the value of what the plaintiff or defendant wins. Here’s a roundup of the latest cases.

Janus, the two headed god that looked to the future and past and gave us the name for January, wouldn’t find much new in the world of disability law if he were contemplating 2023. Cases from the last few weeks look pretty much like cases from the end of 2021 and the end of 2020. Serial ADA litigation is going strong because outcomes depend on the judge assigned rather than the law or the facts. Sober living homes continue to create hostility and litigation as politicians try to balance doing the right thing against the demand of their constituents that they do the wrong thing. And, of course, the cost of victory is often much higher than the value of what the plaintiff or defendant wins. Here’s a roundup of the latest cases.

FHA cases are fact driven

Know your judge when it comes to tester standing

For those keeping score motions to dismiss almost identical complaints filed in the Northern and Western Districts of Texas have reached very different results. In Segovia v. Shahrukh & Shahzeb Inc., 2022 WL 17566267 (N.D. Tex. Dec. 9, 2022) Judge Jane Boyle joined Judge Sam Lindsay in finding that the standard form complaint used by a group of lawyers and their clients was inadequate. Judge Boyle granted leave to amend, so the case isn’t over, but in past cases Segovia and his lawyers have not been able to substantively improve their complaint. As I noted in my last blog, the opposite result was reached in Castillo v. Sanchez et al, 2022 WL 1749131 (W.D. Texas, Dec. 6, 2022) based on an almost identical pleading. District Court decisions are not binding on anyone, including the judge who wrote them, so any strategy concerning the defense of a serial ADA case has to start with knowing the judge.

Calcano bears fruit

If you haven’t been thinking every day about the decision in Calcano v. Swarovski North America Limited you’ll find a review at A short sharp shock – the end of the beginning for serial ADA lawsuits? Judge Andrew Carter found the plaintiff’s allegations in Matzura v. Macy’s Inc., 2022 WL 17718335 (S.D.N.Y. Dec. 15, 2022) and Murphy v. Regal Cinemas, Inc., 2022 WL 17821218 (S.D.N.Y. Dec. 20, 2022) were just as deficient as those in the consolidated Calcano cases and dismissed for lack of standing. Judge Laura Swain did the same in a different Calcano lawsuit, Calcano v. Jonathan Adler Enterprises, LLC, 2022 WL 17978906, at *2 (S.D.N.Y. Dec. 28, 2022). ADA claims based on inaccessible gift cards are meritless for other reasons¹ but standing holdings have a broader impact because they can influence all serial ADA claims, making these dismissals significant for other victims of serial litigation, at least in the 2nd Circuit.

The race to the courthouse – the Anti-Injunction act doesn’t help the loser.

Pushmi pullyu – when is an accommodation unreasonable?

Speaking of two faced, or two-headed animals, in The Story of Doctor Doolittle the pushmi-pullyu is an animal (a llama it appears) with two heads and no rear that can only go in the direction one head faces if the other head backs up. Because the accommodation provisions of the FHA require preferential treatment to create equality of opportunity pushmi pullyu situations are not unusual. One tenant’s emotional support animal may be an annoyance to the neighbor with allergies, for example. Accessible parking creates exactly this kind of problem, as shown in Hume v. Guardian Mgt. LLC, 2022 WL 17834397 (D. Or. Dec. 21, 2022). An accessible parking space necessarily takes almost two ordinary parking spaces because of the required access aisle. If an apartment building does not have sufficient covered parking for all tenants, and has already allocated accessible spaces to other tenants, creating a new accessible space will come at the expense of the two tenants who already occupy the required spaces or at the expense of another disabled tenant whose accessible parking space is taken away from them. In this case the Court found the requested accommodation was not reasonable because taking away an existing tenant’s parking space was an undue burden on the landlord. If that seems like an easy conclusion remember that many accommodations have some negative impact on other tenants and while the FHA requires that housing providers make accommodations, it doesn’t require other tenants to do so. For more about this you can read my blog The horns of a dilemma – landlords, tenants and emotional support animals under the FHA.

Speaking of two faced, or two-headed animals, in The Story of Doctor Doolittle the pushmi-pullyu is an animal (a llama it appears) with two heads and no rear that can only go in the direction one head faces if the other head backs up. Because the accommodation provisions of the FHA require preferential treatment to create equality of opportunity pushmi pullyu situations are not unusual. One tenant’s emotional support animal may be an annoyance to the neighbor with allergies, for example. Accessible parking creates exactly this kind of problem, as shown in Hume v. Guardian Mgt. LLC, 2022 WL 17834397 (D. Or. Dec. 21, 2022). An accessible parking space necessarily takes almost two ordinary parking spaces because of the required access aisle. If an apartment building does not have sufficient covered parking for all tenants, and has already allocated accessible spaces to other tenants, creating a new accessible space will come at the expense of the two tenants who already occupy the required spaces or at the expense of another disabled tenant whose accessible parking space is taken away from them. In this case the Court found the requested accommodation was not reasonable because taking away an existing tenant’s parking space was an undue burden on the landlord. If that seems like an easy conclusion remember that many accommodations have some negative impact on other tenants and while the FHA requires that housing providers make accommodations, it doesn’t require other tenants to do so. For more about this you can read my blog The horns of a dilemma – landlords, tenants and emotional support animals under the FHA.The plaintiff who won everything and got nothing

When a defendant defaults the Court can enter judgment for exactly what the plaintiff includes in the prayer for relief in their complaint, but nothing more. In Hull v. Little, 2022 WL 17818065 (9th Cir. Dec. 20, 2022) the Court did just that. The plaintiff asked for an order requiring the defendant to remediate parking and other architectural barriers but did not ask that the court impose any deadline on the work. The district court gave the plaintiff what he asked for in terms of remediation but included no deadline. The plaintiff asked the Ninth Circuit to fix his mistake, which it declined to do, leaving the plaintiff with an meaningless order.²

The defendant who won and had to pay for it

A note for website owners: mootness starts before you get sued.

Mootness is the best and strongest defense to a Title III ADA claim because, as described in the entry above, if the facility is made accessible the case must be dismissed and the plaintiff gets no attorneys’ fees. The problem is proving the claim is really moot. Where the change is physical courts generally have no problem finding that the situation isn’t likely to recur, but when the change is to an ever-changing website the burden of showing the fix will last becomes much higher. In Langer v. Home Depot Product Authority, LLC., 2022 WL 17738728 (N.D. Cal. Dec. 16, 2022) Home Depot was able to meet that burden because it had a policy of close captioning all of its videos before it was sued and it quickly fixed the one video that slipped through after it was sued. If the policy had been adopted after the lawsuit was filed or there had been more than one uncaptioned video the result would likely have been different. Now is the time to adopt and implement an accessibility policy for your website – after you are sued it may be too late.

We apply the law, but we don’t have to obey it.

I noted Kulick v. Leisure Village Association, Inc., 2022 WL 17848939, at *4 (Bankr. App. 9th Cir. Dec. 16, 2022) mostly for the following striking statement:

The cost of default

In Trujillo v. 4B Mkt. Inc., 2022 WL 17667894, (E.D. Cal. Dec. 14, 2022), report and recommendation adopted, 2022 WL 18027841 (E.D. Cal. Dec. 30, 2022) it was about $3700 in fees and costs plus $4000 in damages and an injuction to fix what had to be fixed regardless. It’s hard to imagine a cheaper settlement given the Unruh Act’s statutory damage provision.

No supplemental jurisdiction here

Gilbert v. Bonfare Markets, Inc., 2022 WL 17968629 (E.D. Cal. Dec. 27, 2022) is another example of a judge who is fairly hostile to serial litigants and will not, in all likelihood, exercise supplemental jurisdiction over Unruh Act claims. Great if you are a defendant in this particular court, but remember that other judges take the opposite approach. Know your judge.

+++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

¹ See my blogs Blogathon – ADA and FHA cases with a little help from my friends. and Quick Hits – Vernal Equinox edition for a very brief history of gift card accessibility litigation.

² I found the appeal puzzling because many ADA plaintiffs show little concern for anything that happens after they get an award of fees. In this case no fees were awarded; in fact, none were requested even though the plaintiff was represented by counsel. Why no request for fees? I couldn’t find a clue in the District Court’s file.